Including Disability Voices! Dorothea Dix & Isaac Hunt

By Dr. Graham Warder, Associate Professor of History, Keene State College, NH

For Massachusetts teachers, the Disability History Museum just became more useful. With the announcement from the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education that the new History and Social Studies Curriculum Framework now includes aspects of disability history, it can be expected that teachers will be looking for appropriate materials to fulfill that new mandate. Some of those materials, particularly for teachers seeking ways to include people with disabilities in examinations of antebellum reform movements, are readily available in the Education Sector of the Disability History Museum. We hope that teachers from Massachusetts, and from across the nation, will take advantage of the resources we provide.

The construction and maintenance of insane asylums was one result of antebellum millennial aspirations. At the reform vanguard was a woman from Massachusetts, Dorothea Dix, who would serve as Superintendent of Union Army Nurses during the Civil War. Dix tirelessly worked to persuade the individual states, and eventually the federal government, to fund asylums built around the concept of moral treatment, the belief that people with psychiatric and cognitive disabilities could be nurtured back to mental health in settings modeled on the middle-class home. People with disabilities could thereby be rescued from the suffering inflicted by their inhumane confinement in local jails and almshouses.

Portrait Photo: Dorothea Dix, circa 1840. Courtesy National Library of Medicine

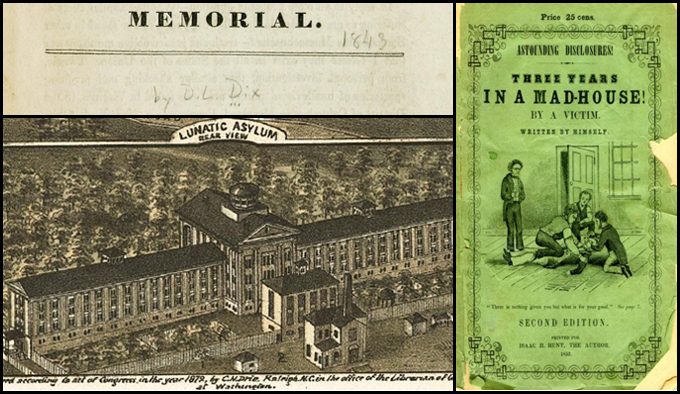

Teachers generally know something about Dorothea Dix. Excerpts from her Memorial to the Legislature of Massachusetts are included in many collections of primary historical documents for the antebellum period. Her Memorial is justly recognized as a classic example of antebellum reform literature, but the focus on Dix alone can obscure other important responses to asylum reform. The DHM’s lesson plan, “Hearing Voices: Did Benevolence Listen?”, includes the words of a variety of people, including Dix, and that blend of voices makes for a far richer encounter with the past, an encounter that raises a number of questions that reverberate with those faced by Americans today. Who gets a say when government acts? What is the role of government in health care? When can government legitimately take away a person’s freedom in the name of the public good? How do people make their voices heard from a position of apparent powerlessness? Who do you trust when public voices conflict?

“Hearing Voices” asks students to examine asylum reform from a variety of perspectives. Dorothea Dix is the crusader who brings her readers with her as she investigates the horrifying conditions endured by indigent “idiots and insane persons” in local facilities. Dix forces her readers to support state-funded asylums as a moral imperative. Isaac Ray is the superintendent of one those state-funded asylums who relies on his medical expertise to assert his authority. He and his fellow superintendents have directly benefited from Dix’s political activism, but he fears that public hysteria and political opportunists could now damage the interests of his profession. Amariah Brigham, the superintendent of the New York State Insane Asylum, explains in the pages of the American Journal of Insanity how moral treatment works.

“Hearing Voices” also includes the voices of those people whom asylum reformers sought to help through confinement. (Historians have traditionally ignored this evidence. We at the DHM believe that is an egregious mistake. It is akin to interpreting the history of American slavery without including the perspectives of the enslaved.) Many teachers may be surprised to learn that the New York State Insane Asylum published a literary journal, The Opal, written and edited by its “inmates.” Published in the 1850s, The Opal allowed those incarcerated within the asylum’s walls to ponder their situation. “Hearing Voices” includes a poem, “Asylum Life, or, The Advantages of a Disadvantages,” that presents the asylum as an almost utopian sanctuary. The author of “Life in the Asylum, Part I” poignantly discovers, “I can’t get out.” Her words are ones of protest.

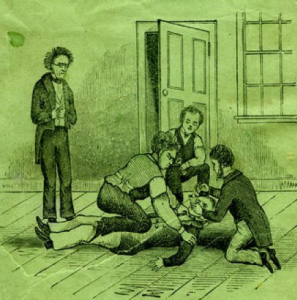

Finally, the lesson asks students to read an excerpt from Isaac Hunt’s Astounding Disclosures! Three Years in a Mad House. Hunt was confined in Isaac Ray’s Maine Insane Hospital and describes conditions there as criminally abusive. Hunt explicitly condemns Dix’s efforts to expand asylums as simply a means by which the number of “victims’ will be multiplied. Hunt says that when he arrived at the asylum, he was “a perfectly deranged man.” How do we judge his words as historical evidence? Let’s let our students decide.

Close up image from Astounding Disclosures cover includes a struggle between individuals inside the facility that Hunt calls a “madhouse” , the Maine Lunatic Asylum in August, Me. Courtesy www.disabilitymuseum.org

The Disability History Museum has a number of other lesson plans under development. We hope to provide teachers with more curriculum materials that will help them incorporate disability history into their courses. Because as the Massachusetts Board has finally recognized, disability history is good history.

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA