Following The Money: Bump, Nutt & Barnum

By Meghan Rinn, Archivist & Cataloger Barnum Museum, Bridgeport, CT

Why sign up to exhibit yourself? It’s a question worth pondering when talking about 19th-century performers with disabilities. Better pay than that offered by other jobs may have been most important, but what were the specific terms and conditions of this kind of employment?

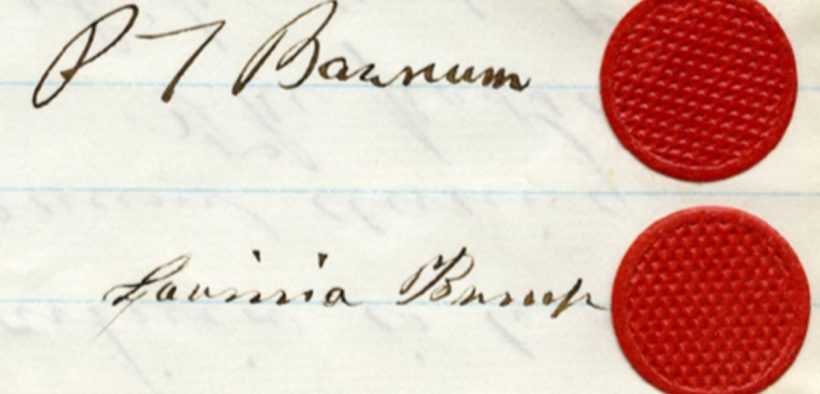

Two contracts housed in Bridgeport, Connecticut, help to shed light on the matter. One is the contract that first signed Mercy Lavinia Warren Bump, soon to become famous as Lavinia Warren and as “Mrs. General Tom Thumb,” to showman P.T. Barnum’s employ. The other is the contract that first brought another little person, George Washington Morrison Nutt, under Barnum’s wing.

M. Lavinia Warren’s contract is one of the many documents that relate to P.T. Barnum and 19th-century circus history in the John Skutel Collection (BHC-MSS 0009). Circus history and disability history often intersect in the 19th century, and for a private collector to have originally owned the document is not out of the ordinary.

Photo portrait of Lavinia Bump, 1863, wearing short sleeved patterned dress and styled hair, side view near table, but Lavinia faces camera. Courtesy, Barnum Museum

This contract is dated December 11, 1862, two months before Lavinia wed another famous performer, Charles S. Stratton, known by the stage name “Gen. Tom Thumb.” In 1859, at about 17 years old, Lavinia had made the conscious choice to end her career as a school teacher in her home town of Middleboro, Massachusetts, and go to work on a river showboat owned by a family member. She relates her first taste of this life in her autobiography, as well as how Barnum approached her about coming to work in his American Museum in the summer of 1862. While Lavinia describes details of the negotiations, along with the fact her parents were concerned that Barnum would simply bill Lavinia as another “humbug”, she does not mention the contract specifics.

Reviewing the document reveals what Lavinia did not. The emphasis is on how Lavinia will be working for both Barnum and the agents he appoints to manage her performances and exhibitions, but more important is the discussion of pay. The four-year contract stipulates an income of $520 for the first and second years ($12,713 in today’s dollars); $620 for the third ($15,194.29) and $780 for the fourth ($19115.39), which could be renewed. Barnum also agreed to cover expenses that related to board, laundry, daily clothes and performance costumes, travel costs (First Class is specified) and the employment of a ladies’ helper for Lavinia. Sick pay is also provided, though not elaborated upon. The last page bears both Barnum’s and Warren’s signatures. Lavinia signs with her proper last name of Bump, which Barnum convinced her to drop from her stage name.

Viewed separately, each contract is informative in that it gives an idea of what Barnum paid his performers and the benefits he offered at the American Museum. Viewed together, the two contracts give a clearer picture of what average salaries were, what perks were commonplace, and what other aspects of a contract were considered standard.

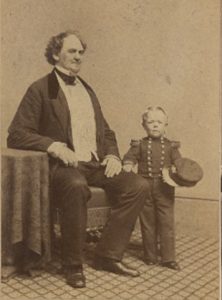

The second contract signs teenaged George Washington Morrison Nutt and his 21-year-old brother Rodnia Nutt, Jr., to P.T. Barnum’s management. This contract was not signed by George, who was just 13 at the time, but rather by the boys’ father, Rodnia Nutt, Sr. The terms, which grant Barnum complete guardianship of both George and and Rodnia Jr., includes details on the salaries for the boys, to be paid weekly.

“Said Nutt agrees that said Barnum shall have the full control and guardianship and authority over his son George Washington Morrison Nutt for the term of five years as hereafter provided that said term of five…”

The annual sums total $624 for the first ($17691.11) year; $728 ($20639.63) for the second; $936 ($26536.6) for the third; $1196 ($33907.96) at the fourth; and $1560 ($44227.78) at the fifth year. Their contract also stipulates how the income from the sales of merchandise was to be distributed. (Lavinia’s contract does not.) As George was still a young boy at the time, Barnum also agreed to provide schooling, and provisions for healthcare were included. To cap it all off, ponies and a carriage were to be awarded to both George and Rodnia, Jr. at the end of the five years. The contract could be revoked by Rodnia Nutt, Sr. if abuse was suspected.

Photo portrait of George Washington Morrison Nutt standing with his hand on P.T Barnum’s knee, 1862. Barnum is sitting, Nutt is not quite as tall as the bend in Barnum’s elbow. Courtesy Barnum Museum

It is interesting to note the discrepancy in pay between Lavinia and George. It is possible that some of Lavinia’s salary might have been lessened in order to pay for her ladies’ companion, something George’s contract does not remotely include, but neither was she required to give Barnum any monetary gifts she received. There are also no specifics in Lavinia’s contract about the profits from merchandise as the Nutt contract outlines. It is likely that this contract might have been a setback for Barnum, as Lavinia’s highly-publicized marriage to Charles S. Stratton undoubtedly sold many more of her cartes de visite (souvenir photographs), with no share to P.T. required! Also notable is the fact that George’s father signed over guardianship rights to Barnum. At age 20, Lavinia was a legal adult when she signed her contract, and thus ceded nothing in that regard.

These two contracts, made only one year apart and signed at the outset of their employment, help illuminate the lives of people with disabilities who worked in museums, sideshows, and similar institutions in the mid- and late 19th century. Scholars, including Robert Bogdan and David Gerber, have debated whether we should view this work as fundamentally exploitative or as self-directed, even liberating, for the people with disabilities involved. Having primary documents that provide not only exact terms, but exact dollar amounts, helps to ground these discussions. Such contracts are not always the easiest documents to find online, and there are likely more stored in circus archives and owned by private collectors yet to be shared. Having these two examples accessible online helps inform the discussions.

More items owned by M. Lavinia Warren and George Washington Morrison Nutt, along with others associated with P.T. Barnum, are available as part of the P.T. Barnum Digital Collection.

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA